Nirmala Dutt: Statements

18 July – 24 December 2023 (Level 5)

“I am an artist first and foremost — not necessarily just a woman artist or feminist artist or political artist.”

Nirmala Dutt (1941–2016) cuts a sharp and unusual figure in Malaysian art history.

She was one of very few women artists in her generation to forge and sustain a practice and presence in the local art scene, and gain recognition beyond. While she preferred not to refer explicitly to gender as a framework, her works addressing social injustice and the atrocities of war highlighted most of all the suffering of women, and children. She was a stridently political artist whose work consistently spoke to power, without fear.

She maintained all these positions, and more, because she was an artist first; that is, her primary role and motivation was expression. Her understanding and concept of art was broad and worldly: while schooled and adept in the languages of the Western modernist painting tradition, she also drew inspiration from the spirit of social criticism within Asian art history and its rebel artists, from Jamini Roy to the Zen monk Sengai to Shitao, Bada Shanren and Zheng Xie (who famously resigned from his position as a magistrate after being criticised by wealthy officials for building a shelter and distributing grain to victims of drought).

It was clear that Nirmala’s practice stood apart from as early as 1973, when she presented a pile of rubbish, a grid of photographs of urban pollution, and a collection of newspaper articles as her entry for the Man and His World competition at the National Art Gallery. She broke ground in her use of found materials, installation, photomontage, documentary photography, and social commentary, especially in shedding light on environmental issues. Yet her work may remain unfamiliar to many today, even though she was tutored, defended and championed by some of the most influential figures in modern Malaysian art. It is perhaps her tense position on the threshold between outsider and insider that gives Nirmala’s work an added sense of daring and freshness.

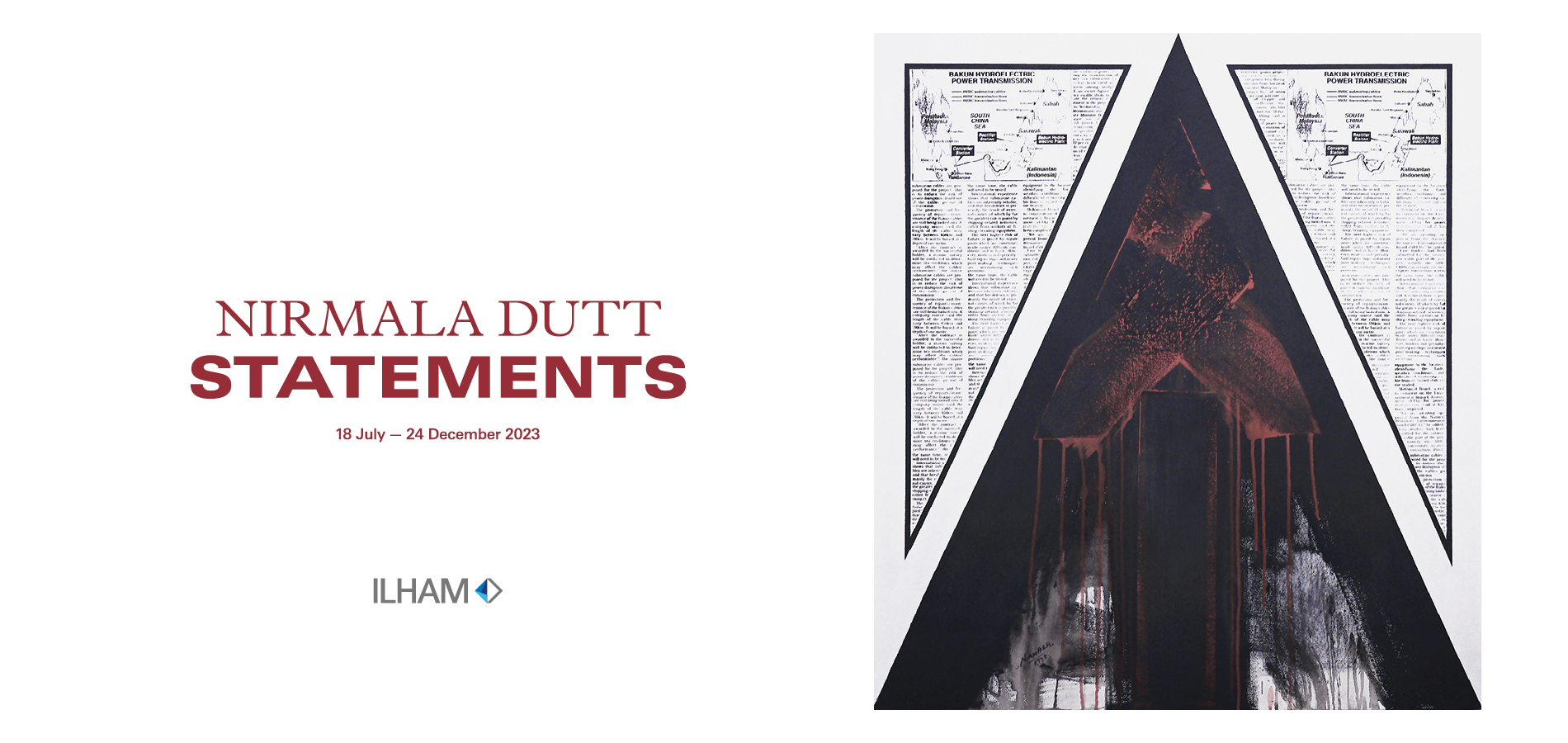

In this exhibition, major series of Nirmala Dutt’s works are brought together as a presentation of “statements”, as she herself titled her first major body of works from 1973 to 1979. The works that followed the text and photo assemblages of Kenyataan/Statements are mainly series of paintings on canvas, often involving silkscreen, found text and images, and gestural as well as hard-edge elements, with later experiments in installation and mail art. In each series, Nirmala addressed a specific subject, often triggered by a current event or observation, with recurring images and strategies allowing us to build connections and intuit themes across them.

The exhibition unfolds into three broad sections.

At the heart of the gallery, there are works that speak of the personal and the domestic, of her position as “artist” and the perception of “woman”. The right section of the gallery focuses on her works which reveal the human and environmental costs of building the supposedly “progressive” nation that is Malaysia today. Presented here are her series on pollution, the plight of squatters and urban poor, the displacement of communities for development, the stripping of nature and commodification of culture, and the vanity of the nation’s “Great Leap Forward”, spanning the 1970s to 1990s. To the left, her paintings, made in parallel during the 1980s and 1990s hold up to us the victims of global conflict and racial violence through series after series - Anak Asia, Vietnam, Africa, Beirut, Bosnia - and lambast the geopolitical powers and machinations that created them. Finally, in her last major body of work, Nirmala was moved to find expression for the tragedy of the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 whose reverberations were felt the world over. We experience not only the powerful charge of an artist’s emotional response but also what it was like to live through a time of overwhelming change and difficulty.

We can read Nirmala Dutt’s “statements” as statements of protest against the violence carried out by man against the environment and his fellow human beings. Or we could read them as witness statements, where the artist is not merely a bystander but actively gathering evidence of and bearing witness to the injustices and tragedies of her time. Or as warning statements, of the consequences of human greed, ambition, hypocrisy, and carelessness. On another level, they are also a statement of her own existence within it all, a record of the events of her time and her deeply-felt responses to them. Each gesture of her brush is an indictment. Today, as climate change accelerates, a new cold war brews, and indigenous communities continue to struggle for their land and rights, and urban development shows no sign of slowing, Nirmala’s calls to conscience remain more urgent than ever.

2015-2025 © ILHAM GALLERY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WEB DESIGN BY TOMMY NG